Addressing Funding Gaps for Wellbeing in Higher Education

These barriers to funding wellbeing include limited public or state funding, pressure on student fees, demands for basic needs (for example housing, daycare, or food pantries), prioritization on other key areas within campus life (such as academic research), outdated standards, and much more. According to National Association of Student Personnel Administrators, 72% of student affairs professionals said the mental health of students and employees worsened during the past year.

Our research also revealed that numerous administrators contend that there is insufficient data, research, and quantitative information available regarding the advantages of wellbeing-oriented spaces and programs. This scarcity of evidence poses a challenge in obtaining approval for funding these initiatives. We hope the research from EOC 4.0 can be a bevy of evidence to help administrations allocate more funding toward wellbeing.

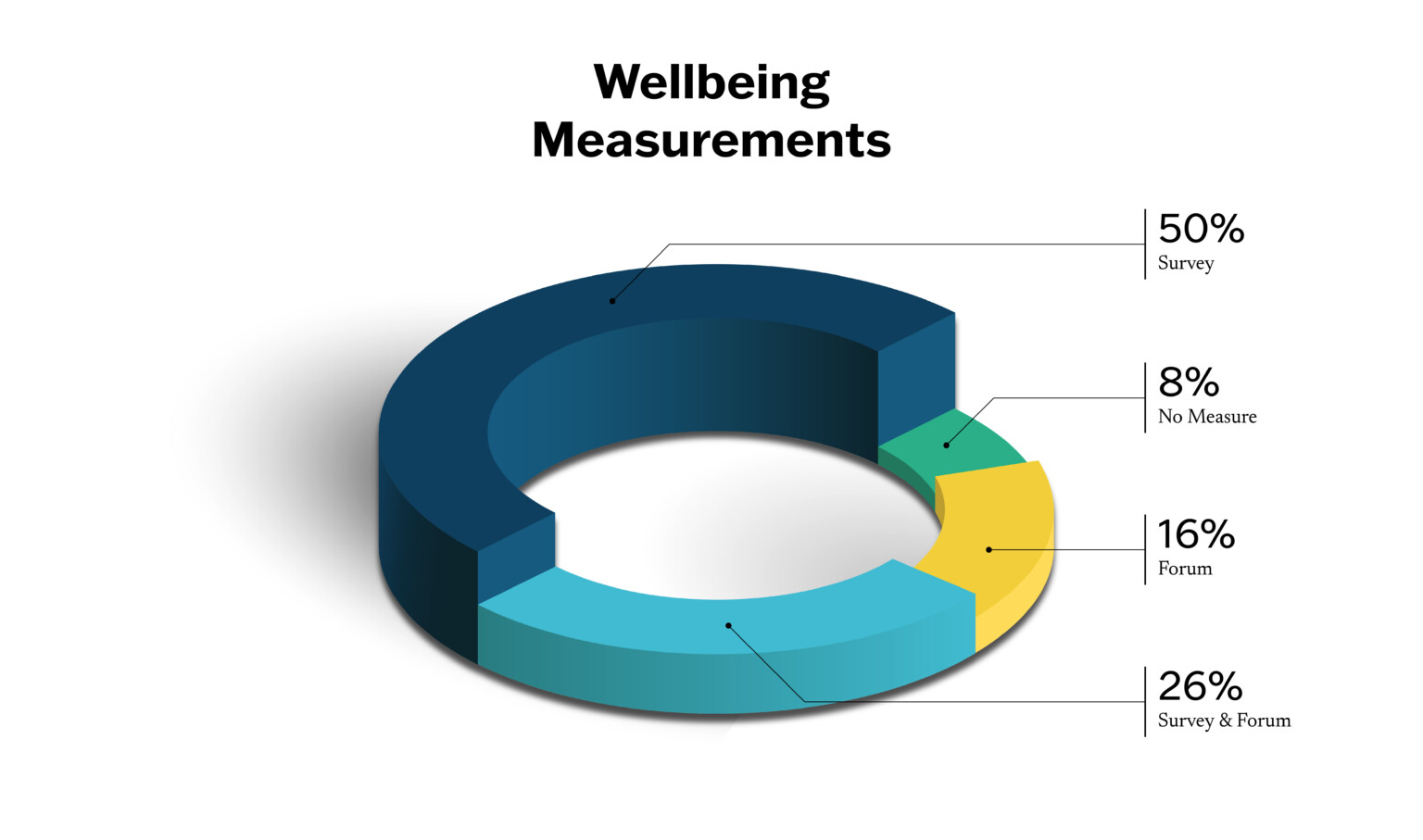

Until administrators have access to a comprehensive body of national research data to support their case for wellbeing funding, many institutions are already taking steps to assess wellbeing in two ways:

- Student surveys administered during fall orientation, upon class withdrawal, or through tools like the National College Health Assessment provide an important means of collecting data behind student preference. For example, since 2016, Bucknell University has conducted an annual well-being survey with an impressive response rate of 63%. This survey aids in pinpointing students’ primary needs and determining which areas on campus can be tailored to enhance well-being. Additionally, hosting town halls, focus groups, or forums with students provides a platform for them to directly communicate their needs to administrators, reducing uncertainty about what students require.

- Just as important, space utilization and outcome-focused measurements gather wellbeing data that focus on the performance of wellbeing on campus. Metrics around graduation rates, campus safety, and the utilization rates of student services like food pantries, financial and counseling services, amenity spaces, and more provide a critical piece of the funding puzzle. In our research, we learned that campuses are investing in space utilization studies to build a strong case for the impact of improving space to provide programs for student wellbeing.

When making the case for funding, EOC 4.0 revealed that institutions that had both a shared definition and measurement of wellbeing on campus cited higher instances of programs and spaces that meet student needs. It is evident that students who experience higher levels of wellbeing on campus tend to be more engaged, achieve greater academic success, and thrive in their pursuits beyond their academic journey as they transition into independent life beyond higher education. The imperative need to act and allocate resources towards wellbeing is pressing, benefiting not only current students but also those who will follow in their footsteps in years to come.