Addressing Societal Issues with Adaptive Reuse

Social

Activating vacant buildings to grow community, in community supports positive social change. The Greater Whittier LGBTQ+ Community Center transformed a vacant former probation office into a vibrant advocacy and care center in an innovative model funded by a state grant and operated by the Los Angeles Centers for Alcohol and Drug Abuse. This center fills a critical gap in the Los Angeles County care system; people who live in and near Whittier previously had to travel to either Los Angeles or Long Beach, with limited public transit options. Now, hundreds of community members have access directly in their community.

Like healthcare, education is evolving: changing curriculum, next-generation learning, and increasing pressure on long-range financial models are all shaping schools. Population fluidity creates pockets of megagrowth in certain school districts, contrasted by contracting retail viability.

The need for space is dire for the most vulnerable learners: students aged 3-5 with special needs. Finding space in existing facilities and getting children to schools outside their communities are common obstacles. The award-winning North Kansas City Early Childhood Education Center solves both issues, delivering vital early education to 900 students, 400 with special needs, in a transformed vacant big-box store. “Having the early learning center in the middle of our community creates a true continuum of services to meet the individual needs of every child,” says Dr. Katie Lawson, North Kansas City Schools executive director of special programs. This community-centric approach has attention beyond the district.

Then we hear about the kinds of experiences that [students and educators] get to have. I can’t even imagine the impact [the center] will have once the kids are 18, 20, 30 years old. Our hope is that they stay local and continue to be part of our community,” continues Allen.

Economic

Facing delayed permitting, extended material lead times, and construction labor shortages, conversions get research and science to market faster. When challenged to design a growing biotech headquarters in Colorado – which is experiencing shortages in leasable life sciences real estate – we adapted a vacant department store into a high-tech workplace and laboratory.

The shell offered ample square footage, but structural and user comfort challenges. The structure was designed for minimal needs; now additional economized structural elements support rooftop HVAC and a standby generator for backup critical systems supply. The expansive floorplate prevented daylight penetration, which is proven to harm productivity and cognitive function; building envelope improvements now harvest natural daylighting deep into the building’s interior. Big-box retail offers one critical element often missing from offices being converted to labs: loading docks. By designing around this existing building infrastructure, we dramatically improved the company’s commercialization operations.

While life-science companies struggle to find appropriate real estate as their market booms, municipalities grapple with the opposite concern: aging, owned real estate assets that are irrelevant in new operational models. In Phoenix, taxpayers could decide to tear down and remediate a six-story jail that had sat empty for a decade in the heart of downtown, then rebuild, or to invest in the existing structure, adapting it to house the county’s attorney offices. Other firms recommended demolition. Our plan instead transformed a secure, closed, and fortified structure designed to separate individuals from society into an open, welcoming Class-A workspace with daylight and views.

As tourism rebounds post-COVID and digital nomads migrate to capture lower cost of living, adaptive reuse can contribute to flyover states rebranding as destinations and desirable communities. While systems upgrades are typically more complex when converting to residential and hospitality uses, adding innovative design and engineering solutions to the historical value of a building can prove financial feasibility to developers and pour new life into architectural wonders. “Some buildings weave the fabric of a city together. Being able to save those buildings is incredibly fulfilling,” says Senior Principal and Global Hospitality Leader Ed Wilms, AIA.

In Des Moines, Iowa stands the 12-story Surety Hotel – formerly a bank built in 1913. With the help of Historic Tax Credits, we respected the building’s heritage, restoring the coffered ceiling and stair detailing, while adding 137 guestrooms and more. The heart of the hotel is a tavern that has become a favored haunt for guests and locals alike. In Minneapolis, Minnesota, a historic early 20th century flour and fabric mill has been repositioned as a lifestyle hotel with artful abstractions of weaving and flour sifters punctuating exposed industrial materials and timber framing.

Cleveland’s historic Terminal Tower is an iconic urban node whose transformation was cited in a Washington Post article on “America’s best example of turning around a dying town.” With the departure of the building’s anchor tenant, the owner needed to reimagine 12 stories of the 52-story building with an office-to-residential conversion. Nearly 300 units – complemented by modern amenities including fitness and roof terrace – required 57 unique designs due to variable floorplates. Extensive building systems upgrades brought the residences into code compliance for the new use, while key elements of the 1926 tower were preserved in collaboration with the State Historic Preservation Office.

Environmental

Another fundamental societal issue is climate change, and inextricably tied, carbon footprint. A design maxim industry is “the most sustainable building is one that’s already built.” Statistics from a recent American Institute of Architects study are sobering: each year, approximately one billion square feet (about the area of Manhattan) of buildings are demolished and replaced with new construction. According to the EPA, almost 90% of construction debris is from demolition, representing over 500 million tons transported to landfills each year. The Maricopa County jail-to-office conversion reused 1,050 tons of steel and saved 32,500 tons of concrete from being sent to the landfill, at a cost-savings to the county of nearly $70 million. Creating a similar energy efficient office space with the inherent qualities found in the existing structure would have been cost prohibitive.

50-75% of embodied carbon emissions in a building is held in the foundation, structure, and building envelope – all of which are typically substantially retained with adaptive reuse. To demonstrate this carbon savings, our engineers partner with in-house climate strategists to run embodied carbon calculations that compare the saved embodied carbon of reuse to a similar new building, supporting our commitment to the climate-oriented Architecture 2030 and Structural Engineering 2050 challenges. For the Albany Museum of Art, adapting a department store avoided 65% of the embodied carbon emissions compared to a new carbon-intensive building. On this building alone, that equates to 1,600 metric tons of avoided carbon emissions.

1+1=3

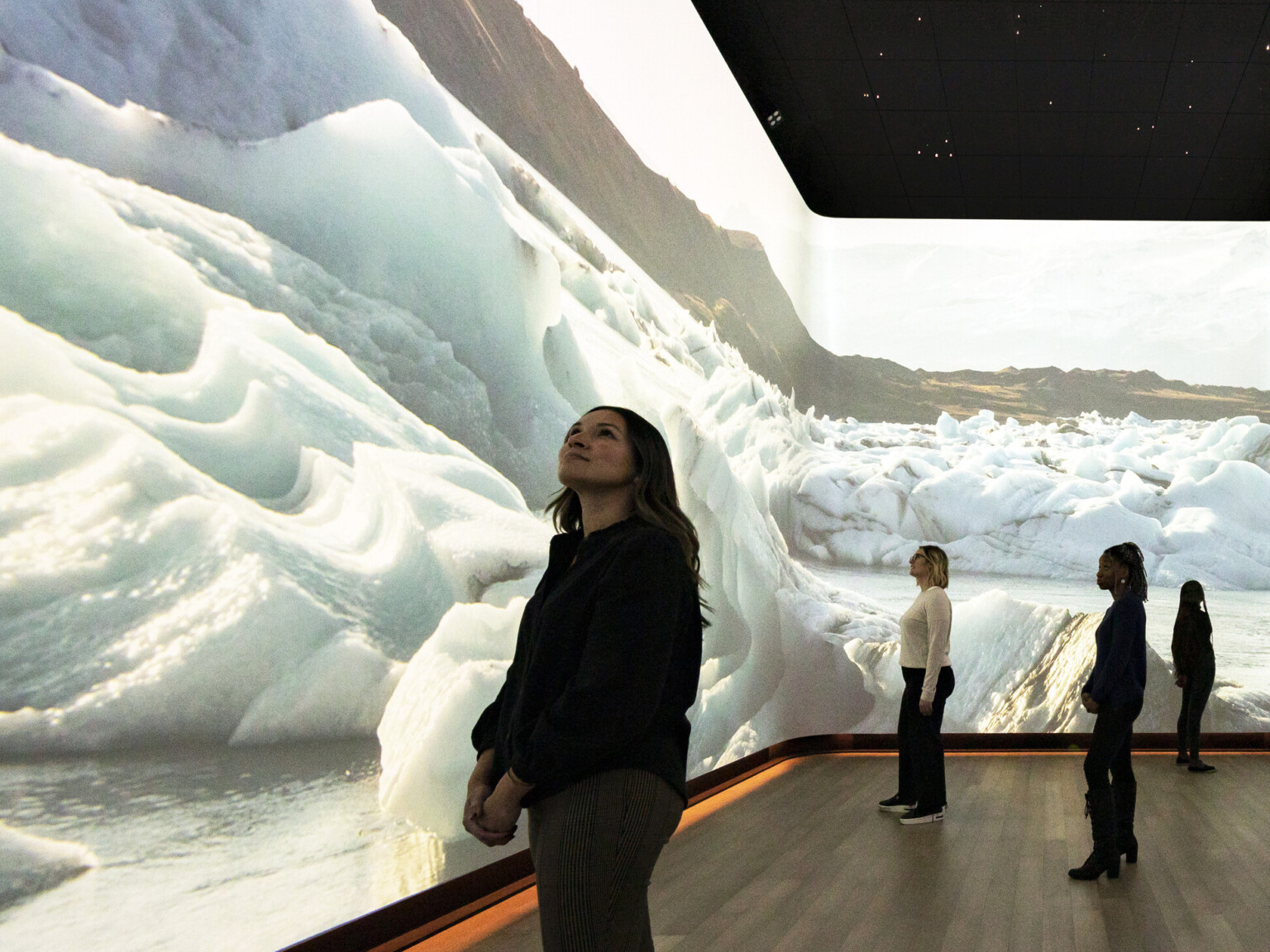

Carbon savings are one part of the Albany Museum of Art’s story, but social impact is another key benefit. Following a devastating tornado, the museum needed a new home, and a long-vacant Belk department store was donated. Relocating to downtown held the opportunity of repositioning the museum and the vacant store as an inclusive community hub that aligns with the community’s values.

And Principal and K-12 Education Leader Ian Kilpatrick, AIA, NCARB, links the social impact of the North Kansas City big-box to school conversion to economic benefit. “When a project needs to happen quickly, especially at this scale, adaptive reuse is often the most viable route. Design to opening took less than a year – nearly halving the typical new build timeline. It’s also much more cost-effective. You get twice the amount of space at a similar cost to a school built from scratch.”

Often, the social, economic, and environmental impacts of adaptive reuse are interlinked. Our in-house architects, interior designers, engineers, and specialized high-performance design, preservation, acoustics, audiovisual, landscape, lighting, and experiential design professionals effectively evaluate existing building stock to make recommendations that maximize all three, helping clients and communities thrive.”